Amidst the chaos of World War II, a Nazi spy ring operated covertly on Long Island, employing tactics ranging from sophisticated radio communications to the use of double agents. As Allied forces intercepted transmissions and orchestrated sting operations, the battle for intelligence supremacy unfolded on American soil. It was the largest espionage case in U.S. history and would be counted among FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover's major successes. And Long Island had a huge part in it. Here, we delve into ten captivating facts about this audacious espionage network and its impact on the war effort.

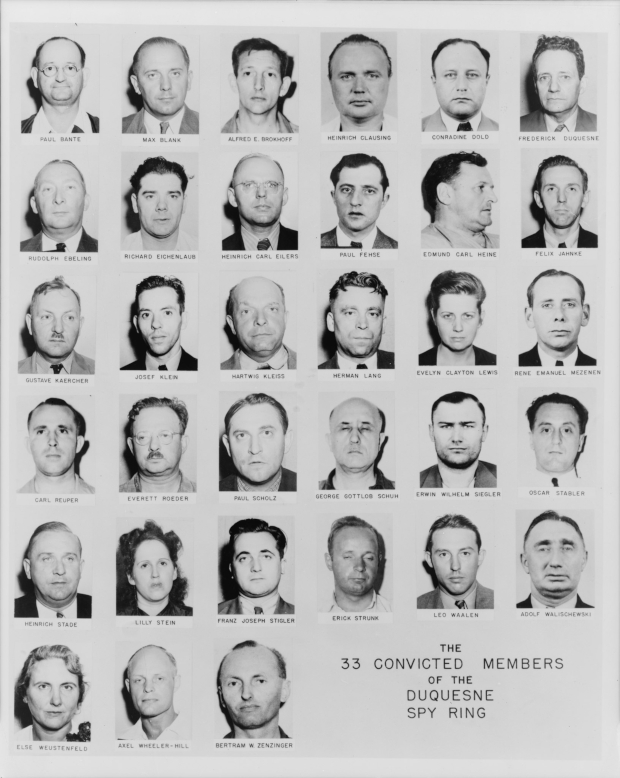

Duquesne Spy Ring: The Duquesne Spy Ring was a Nazi espionage network operating in the United States during World War II. Led by Fritz Joubert Duquesne, a South African-born Nazi agent, the ring comprised more than 30 individuals who gathered intelligence and conducted sabotage activities on behalf of Nazi Germany. The network was discovered and dismantled by the FBI in 1941, leading to the arrest and conviction of its members. It remains one of the largest espionage cases in U.S. history. Many of the members of the spy ring operated in and around the New York metropolitan area, which included Long Island. They used Long Island as a base for their espionage activities, including transmitting messages via shortwave radio to Nazi Germany. Additionally, some members of the spy ring had ties to the pro-Nazi German American Bund, which had headquarters in Yaphank.

Infiltration Tactics: The Nazi spy ring on Long Island during WWII employed various infiltration tactics, including using false identities, blending into the local community, and even posing as ordinary citizens to gather intelligence.

Radio Transmissions: Engineers from the FBI Lab covertly constructed a clandestine shortwave radio transmitting station on Long Island. By May 1940, Bureau agents successfully established communication with a German shortwave station overseas. This Long Island-based radio facility operated as a vital conduit for communication between German spies operating in New York City and their handlers in Germany, sustaining uninterrupted contact for 16 consecutive months. Utilizing this channel, FBI agents transmitted over 300 convincingly authentic messages, while also intercepting approximately 200 messages from the Nazi operatives.

Covert Operations: The Nazi spy ring conducted covert operations under the guise of legitimate business activities, such as operating front companies or engaging in seemingly innocuous transactions. This allowed them to conceal their true intentions while carrying out espionage.

Counterintelligence Sting Operations: Allied counterintelligence agencies, aware of the Nazi spy ring's presence, set up elaborate sting operations to entrap and apprehend its members. These operations often involved intricate deception tactics and surveillance techniques.

Double Agent William Sebold: William Sebold, an American of German origin, was coerced into espionage by Nazi intelligence during a visit to his mother in Mülheim in 1939. Threatened with exposure for a past offense, he reluctantly agreed to cooperate. Returning to New York, he established a front company, "Diesel Research," to communicate with Nazis. However, Sebold had informed the U.S. consulate, making him a double agent from the start. Double Agent William Sebold disclosed receiving $22,000 from Nazi Germany over two years to pay network members.

Collaboration with Sympathizers: The Nazi spy ring collaborated with sympathetic individuals within the local community who shared their ideology or were susceptible to coercion, providing them with support and aiding their clandestine activities. The National German American Bund, initially established to advocate German values and foster assimilation into American culture, gained prominence on Long Island. This alliance also forged partnerships with the Christian Front and Protestant Civic Welfare. Unfortunately, over time, the movement descended into espousing Nazism and anti-Semitic sentiments.

Everett Roeder: A Nazi spy from Merrick, Roeder held a prominent engineering position at the Sperry Gyroscope Company in Garden City. His role provided him with access to critical technologies including bombsights, long-range guns, and state-of-the-art autopilot systems. On the morning of Saturday, June 28, 1941, the tranquil community of Merrick found itself swarmed by FBI agents and local law enforcement, converging on 210 Smith St. Roeder, the homeowner, was led out of his residence in handcuffs. According to reports, the FBI found 100,000 rounds of ammunition in his basement.

Femme fatale, Lilly Stein - Born in Vienna, Austria, the twenty-four-year-old, had relocated to New York using a passport facilitated by Nazi military intelligence and a visa arranged through a romantic connection within the State Department. While employing her feminine wiles to cultivate her own sources, she also transmitted intelligence provided by a motley crew of self-appointed spies. Her address was used as a return address by other agents in mailing data for Germany. Stein pleaded guilty and received sentences of 10 years’ and two concurrent years’ imprisonment for violations of espionage and registration statutes, respectively.

Benson House in Wading River: The Benson House was used to thwart Nazi spy efforts and control information sent to the Nazis by supposed German spies who were really American agents. Shortly after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, the FBI repurposed Benson House into a covert radio facility.

From there, encoded messages were exchanged with German intelligence agents in Hamburg, Germany. Unbeknownst to the Germans, they were actually communicating with FBI operatives. From January 1942 until the conclusion of the European war in May 1945, FBI radio operators sent a mixture of accurate and false information to deceive the Germans. In 1943, counterintelligence aimed to mislead German troops away from eastern and Italian fronts, while in 1944, misinformation regarding D-Day plans was disseminated. Additionally, false intelligence concerning Allied intentions to invade Formosa and the Kuril Islands was relayed to Japanese forces.

The operation involved installing several large shortwave radios within the house. To avoid suspicion due to increased electricity consumption, a Buick car engine was utilized in the basement to supply power, with a muffler dampening noise. Despite the need for large antennas placed outside, they were concealed by trees, aided by the house's secluded location at the time.

The Nazi spy efforts were not very effective at the end of the day: According to an article, “Nazi Spies in America!”, the term "Nazi spy ring" carries a chilling undertone, yet in reality, Nazi intelligence efforts within the United States often appeared more like a farce than a serious threat—reminiscent of Colonel Klink rather than a formidable supervillain. The German regime never prioritized the establishment of a robust spy network in the US. Nazi operations remained small-scale and peripheral for the most part. As the 1930s drew to a close and the specter of war loomed larger, the opportunity to build a substantial network evaporated. Nazi intelligence consequently relied on a motley crew of amateur agents, none of whom possessed the necessary skills for effective espionage.

Smaller spy rings: After breaking up large spy rings, Long Island faced smaller ones during the war. Frank Hart of North Babylon was an example. He joined the Nazi party in Germany before returning to enlist in the Army Air Corps, where he leaked military plane weaponry intel to Nazi agents.